As Curtain Closes on Ziegfeld, Remember Dorothy Parker and the Ink She Spilled

The Ziegfeld name is back in the news in New York. It is for a small item—that is only important to a few people—the few souls who like going to a movie theater in a cavernous space of more than 1,000 seats. Newspapers and bloggers in New York are probably writing about the Ziegfeld name for one of the last times, and that is sad. It is because the movie theater that was built in 1969, not far from his last venture, the Ziegfeld Theatre on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Forty-ninth street, is to be gutted and closed, and turned into a space that will no doubt be holding the 2016 Holiday Party for Cablevision.

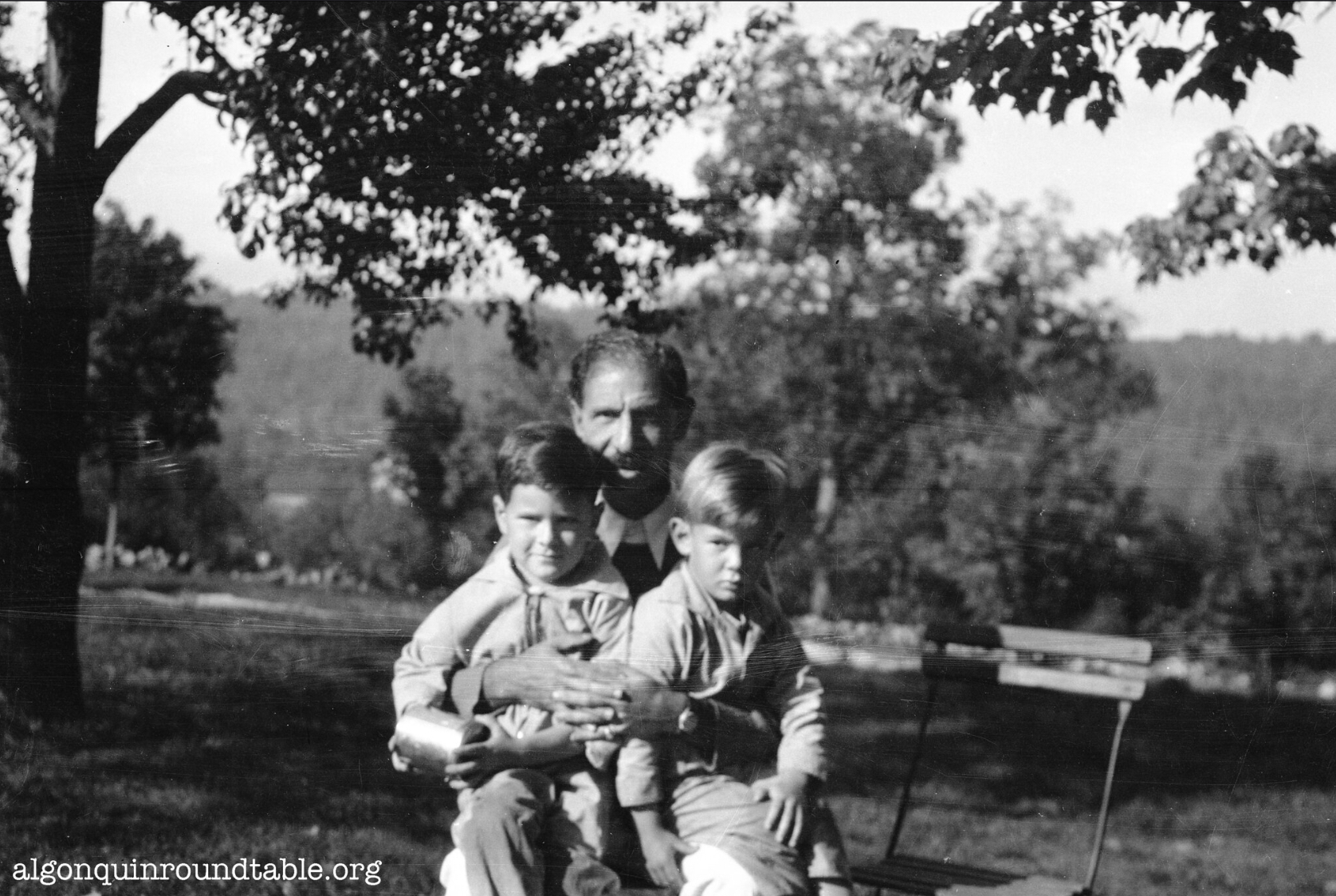

Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. (1867-1932) was one of the most well-known men of his era, a showman who influenced show business and pop culture, but is rarely talked about today. Seeing his name back in the news, for a movie theater demise that has a tangential tie to his life, it brings to mind the fact that he was as popular as any headline-maker of his time in the speakeasy era. Of course Dorothy Parker wrote about him; her career as theater critic for Vanity Fair and Ainslee’s was intertwined with his.

Still we’re groggy from the blow

Dealt us—by the famous Flo;

After 1924,

He announces, nevermore

Will his shows our senses greet—

At a cost of five per seat.

Hasten, Time, your onward drive—

Welcome, 1925!

Parker was, like many theatergoers of her era, a faithful attendee at the Follies. It was an annual tradition for twenty years, and launched the careers of scores of stars. Reading her reviews of the shows, which are collected in Dorothy Parker Complete Broadway, 1918-1923, you can see she had sheer delight in being in the audience. The Follies during World War I took patriotic zeal to new heights, and it’s really a shame there are no color photos or films to show just how mind-blowing the shows on Forty-Second Street could be. But we have her review from 1918, that contains:

There is one great moral lesson to be derived from the Follies and that is this: if we must have our patriotic spectacles of an evening, Mr. Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., is unquestionably the man to produce them. Any more dazzling stage pictures than those which go to make up the Follies, I have never beheld. They deserve every word that the advertisements say of them, and more besides. And I never knew there were as many pretty girls in the world as they are gathered together on the New Amsterdam stage; really, I saw so many beautiful women in the course of that one evening that it was a positive relief to go home and look in the mirror.

A couple years later, after Ziegfeld in a manner caused her to lose her job (more below), Parker was on fire when she went over for the new edition of the Follies. For 1920 in Ainslee’s, she wrote:

Brighter things by far are in store for the visitor to the New Amsterdam Roof, where the Nine O’Clock Frolic and the Midnight Frolic nightly transpire. It speaks much for Mr. Ziegfeld’s art that his roof entertainments seem as good in these sarsaparilla-saddened nights as they did back in those golden times when one could still obtain one’s heart’s desire, if one knew the waiter, or in those only slightly less golden times, of flasks on the hip.

Where the Ziegfeld girls come from will always be one of the world’s great mysteries; certainly, one never sees any like them anywhere around. The line-up in the last Frolic shows that Mr. Ziegfeld’s eye is as unerring as ever. He has not relied entirely upon home talent for these new shows; there are importations from Paris and London, respectively, in the persons of Mademoiselle Spinelly and of Kathleen Martyn, both of whom do much to strengthen the good feeling between the United States and her leading Allies. The comedy part of the proceedings is mostly entrusted to the competent care of W. C. Fields, the delightful little Mary Hay, and Fanny Brice. Many of the songs are delivered by Lillian Lorraine, who raises the Frolic’s standard of pulchritude even higher, but who brings the vocal average down to about minus seventeen.

Parker was a fan of the Follies, produced annually by Ziegfeld. However, she took great delight in needling him every chance she got. She praised the shows, generally enjoying the music and comedy, the showgirls, and comedians. But Ziegfeld himself never got a pass. When Ziegfeld divorced the glamorous Anna Held in 1913 and married Billie Burke, it gave Mrs. Parker a second opening to wound him. She generally praised Burke’s acting, as the reviews show. However, as Burke took part after part in her husband’s shows, playing ingénue roles into her thirties, Parker had enough. Burke was 34 playing Juliet, and this set the critic’s teeth on edge. Finally, when Ziegfeld cast his spouse in Caesar’s Wife, a W. Somerset Maugham comedy, she couldn’t take it any longer. Burke, she wrote, “looks charmingly youthful” for being 35. Parker went on to say,

She is at her best in her more serious moments; in her desire to convey the girlishness of the character, she plays her lighter scenes as if she were giving an impersonation of Eva Tanguay.

Bang! Ziegfeld hit the roof. Comparing his wife to Tanguay was akin to calling her the era’s Lady Gaga. He complained to Condé Nast, who left the matter to creative director Frank Crowninshield. Over tea and scones at the Plaza Hotel, Parker was fired in January 1920. She finished out her commitments during the next several weeks, meanwhile lining up her next bread and butter job.

It is a shame that nobody will ever buy a ticket to see entertainment—even if it’s a Star Wars sequel—any longer at a theater bearing the Ziegfeld name. But it’s been a long, long time since the man had any influence in the city, so if they keep it around on a marquee for a corporate party space, that means nothing. Ziegfeld was about The Show, and if his name hangs on a party room where the sales director can flirt with the project manager, that won’t be the same.