On Independence Day I’ll be climbing the 215 steps up to the pedestal of the Statue of the Liberty. I’m making five trips in five consecutive days, down from four trips last week. As a licensed tour guide, I’m among the lucky few who get to visit the most famous landmark in the country for my “job” so often. Taking visitors to Liberty Island and Ellis Island is an incredible privilege. When I began leading frequent trips to Lady Liberty it coincided with publication of my World War I book. Visiting the modest museum inside the pedestal (soon to be replaced by a more grand one) visitors are presented with large amount of Great War imagery and ephemera, a discovery I wanted to share with others who do not get to visit the Statue of Liberty as often as I do.

What I say on my tours—and this may differ from other guides because I wrote my own script—is to show how Columbia was replaced by Lady Liberty as the feminine symbol of the United States. I first became aware of this while visiting U.S. cemeteries such as Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn. That is Columbia’s face carved on the 19th century iron gates, not the Statue of Liberty. What the museum shows is the process where the Statue becomes not such a symbol of Liberty, which is what the gift from France was meant to be. Or it’s next phase, a symbol of immigration and a new life in America, as the Lazarus poem celebrates. It is World War I.

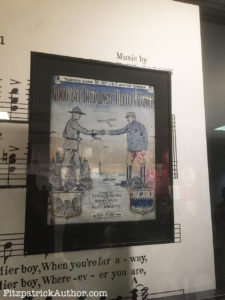

The museum uses the sheet music of popular songs composed on Tin Pan Alley to show the change. The Statue of Liberty is usually on the cover. Posters for bond drives and recruiting are common enough. It is here that Lady Liberty takes on a human form, pointing, walking, and talking. In some she bears a resemblance to Zelda Fitzgerald or an apple-cheeked chorus member of the Ziegfeld Follies.

The centerpiece of the poster display is the Fourth Liberty Loan Campaign. With the headline “That Liberty Shall Not Perish From the Earth,” the 1918 painting by Joseph Pennell shows German biplanes bombing Manhattan, the city skyline in flames. The incredible imagery features the Statue of Liberty destroyed, her decapitated head resting in New York Harbor.

I’m always drawn to artifacts, the tangible items you could hold in your hands (if they were not kept behind glass in locked display cases). This is what you’d hope to find in an attic or flea market. By far my favorite items in the museum, which I’m sure most visitors pass by without noticing what they are, happen to be trench art. These are pieces made by soldiers or others during the war. The museum has two excellent specimens: two spent artillery shells, fashioned into Statue of Liberty motifs. The artwork is stunning, and whoever created it a century ago probably had not idea it would one day be inside a museum underneath Bartholdi’s statue.

World War I almost was the end of the Statue of Liberty, if anyone studies the Black Tom Wharf explosion of July 30, 1916. The ammunition depot explosions in Jersey City were directly behind the Statue (where Liberty State Park is today). Black Tom was a mile-long peninsula and was the most important spot in the nation for the transfer of guns and munitions to Allied ships. On that night, saboteurs (never caught) blew up fifty tons of TNT and 100,000 tons of ammunition. The Statue of Liberty and Fort Wood suffered significant damage.

One does not need any reason to visit the Statue of Liberty. But if you need one more push to get a ticket and board the ferry, looking for the World War I items is another one.

For more history stories, pick up World War I New York: A Guide to the City’s Enduring Ties to the Great War (Globe Pequot). Available here.