I am really happy my friend Michael Cumella has pushed Woodlawn Cemetery to finally put a gravestone on the final resting place of singer Nora Bayes. The unveiling is Saturday, April 21, at noon at the landmark cemetery in the Bronx. A nice New York Times story explains the whole rigmarole about why the famous singer never got a stone when she died 90 years ago.

But this is just the first of a number of other unmarked graves in Woodlawn that need gravestones.

I know something of this subject, because in November 2016 I tried, unsuccessfully, to get a project off the ground to not only mark Nora’s, but also eight others from the Jazz Age. My friends and I produced a whole project plan, presented it to the Woodlawn Conservancy, and never got any traction.

It was disappointing to me, and I’m sure also to my two friends: Michele who writes the Tales of a Madcap Heiress and is an expert on Olive Thomas, and the incomparable mountebank TravSD, who writes the indispensible Travalanche.

These are some of Woodlawn’s forlorn former entertainers (and spouses) of the past who are in unmarked graves and need ones placed on their final resting places. Of the eight, five were black.

(1882-1922)

It is amazing that a circus performer lacks a grave marker. You live in the limelight and then are forgotten in death. George Auger was born in Wales and was billed at 8-foot 4 inches (or taller), but according to TravSD was 7-feet 4.5-inches. He got his nickname from a P.T. Barnum hoax, but there was no connection to the Cardiff Giant. Auger came to America and was a Ringing Brothers circus star in 1903. He was frequently cast with smaller actors to make him look taller. Auger tried to retire to Connecticut, but one more tour was too much for him. He lies in an unmarked grave.

Nora Bayes, singer

(1880-1928)

The unmarked grave to Bayes is finally about to end thanks to the work of Michael. It’s perfect timing: Her biggest recording was “Over There” written by George M. Cohan (another Woodlawn permanent resident, but in a massive mausoleum). This was one of the most popular songs of World War I, and this year is the centennial of the Armistice.

Willie Europe, jazz widow

(1877-1930)

On January 5, 1913, James Reese Europe (1881-1919) married Willie Angrom Starke, a widow of some social standing in New York’s black community. He was the WWI bandleader of the 369th Infantry Regiment Band, the Harlem Hellfighters. He came out of the Great War as one of the biggest celebrities. But tragedy struck when a deranged drummer murdered him. The bandleader is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, final resting place of countless heroes. Depending on the rule changes, Willie is eligible to be buried with her husband. That would be a ton of paperwork, and a disinterment and cremation requirement, so it would be a lot easier just to erect a grave marker for Willie.

(1889-1958)

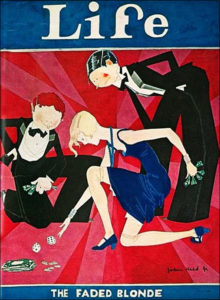

The broken gravestone of this titan of Jazz Age art is heartbreaking to me. Held, more than any other illustrator defined the look of the Flapper. His illustrations were incredibly popular and he made, and lost, a fortune in the 1920s. He drew for The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and countless other publications. Somehow, his grave marker was broken, probably by a lawnmower. It lies in pieces by his grave. His wife has an unmarked grave too.

Black Herman (Benjamin Rucker), magician

(1892-1934)

The unmarked grave of this black magician is sad, because his act was to come back from the dead. As Trav writes, “Black Herman was not just a magician (although he used lots of magic tricks), but presented himself as a genuine Voodoo Witch Doctor, capable of healing the sick and raising the dead.” Maybe the public thought he’d come back?

Nina Mae McKinney, actress

(1912-1967)

No gravestone marks the “Black Garbo” who was one of the first international black film stars. Nina went to Paris in the inter-war period and became a star in Europe in the 1930s. A striking beauty, she made a name overseas at the time racism kept her out of American movies. When she went to Hollywood, she only could get minor roles and parts. She died at 54 of heart disease and never got a gravestone.

(1890-1969)

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (1878-1949) was a pre-eminent tap dancer and early African American film performer. Fannie Clay Robinson was his second wife and business manager. They were married from 1922-1943 and she is credited with managing the great entertainer’s career. The couple founded the Negro Actors Guild of America, which advocated for the rights of African-American performers. They split up when Fannie divorced him in Reno. Bill remarried, and is buried at the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. When Fannie died in 1969, she left a safe deposit box that contained $11,000 in cash (about $75,000 today). Enough for a grave marker, yet none was purchased.

Kid Sneeze (Irving Williams), pianist

(1886-1946)

In 1910 he was one of the founding members of the Clef Club, the first union for black musicians and entertainers, cofounded with James Reese Europe. He was the pianist for what was considered the “smart set” of New York. As Tom Fletcher wrote in 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business (1954), he “was known by the nickname of “Kid Sneeze,” inherited indirectly from his older brother who had a peculiarly shaped head. Al Brown, manager of the Douglas Club, a professional club in New York, had tagged the older Williams brother “Sneeze” so Irving, whose head wasn’t as large but was similarly shaped, was called “Kid Sneeze” and the name stuck to him all through his career.” Today Kid Sneeze is remembered as one of the many black musicians interred in Woodlawn, but he lacks a grave marker.

Olive Thomas, actress/showgirl

(1894-1920)

Michele best tells the story of this sad mausoleum here. She has been trying for years to get the Pickford memorial in better shape. But the real “ask” was to get a footstone placed that had Olive Thomas’ name included. Olive was married to Jack Pickford and was a silent movie star and Ziegfeld Follies girl. She is all alone, and no marker exists to remember her.

Perhaps now that Nora Bayes has a gravestone, other kind souls will take up the cause of these other eight who do not have their names on their gravesites. I am too busy to try to revive the project, so I hope someone else will.

***

Kevin Fitzpatrick is the author of World War One New York: A Guide to the City’s Enduring Ties to the Great War (Globe Pequot Press), which has a chapter on Woodlawn Cemetery.