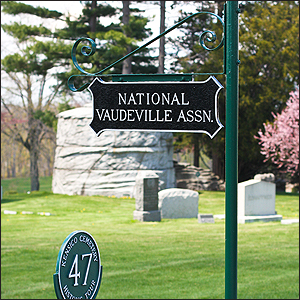

The National Vaudeville Association grave of Edward Gallagher, in Kensico Cemetery. He was one half of the act Gallagher and Shean. Their act consisted of feeding each other lines, with the usual climax of each joke ending with, “Absolutely, Mister Gallagher?” and Gallagher replying “Positively, Mister Shean!”

Project Updates and Biographies are posted here.

Twenty-eight miles north of Forty-second Street is Kensico Cemetery. Interred there are hundreds—perhaps more than a thousand—stage performers and associates. These men and women were onstage in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. I stumbled across perhaps three hundred old vaudeville entertainers in a little-known plot, long forgotten about, laid out in neat rows in the historic cemetery. The Kensico Vaudeville Project will tell some of their stories.

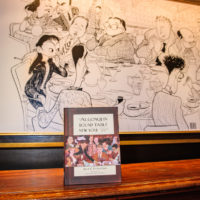

I found the graves by accident. I was visiting more famous Kensico permanent residents, such as Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. (whom many of the deceased worked for) and his wife, Billie Burke, Marc Connelly and Margalo Gillmore (both Algonquin Round Table members and Broadway veterans). The cemetery is stunningly beautiful and the landscaping, architecture, and history on par with Central Park.

Kensico contains the Actors’ Fund Plot, denoted by a remarkable stone obelisk, perhaps fifty feet high, with the symbol of Ra. The Egyptian sun god represents rebirth and the afterlife. Hundreds of thespians are buried around it. But a short walk away is roughly a half-acre of neatly trimmed grass, that if you were walking past and didn’t see the small sign denoting “National Vaudeville Association,” you’d miss it.

Some background about the project and the cemetery:

I didn’t know anything about American vaudeville until I read the landmark book by Trav S.D. No Applause—Just Throw Money, The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous (Faber and Faber, 2005). It opened my eyes to an entire unknown world of live entertainment that existed for about 75 years. I thought that by visiting these vaudeville graves I’d meet the people in Trav’s book. But I was wrong. In most cases, these names are so obscure that they are not mentioned in the book, or any other books. Likewise for the National Vaudeville Association (N.V.A.). First I paid my respects, and then I began the research. But first the history of how these folks ended up here, which has never been written about before.

Let’s start with the cemetery. In 1889, seven residents met in White Plains (county seat for Westchester) to organize the Kensico Cemetery as a rural cemetery association. This was a very popular trend in the middle 19th Century, when landscaping and natural beauty were believed to be crucial to respectful final resting places. Lakes, streams, hills, and wooded sections are always included. In 1889 Westchester County approved the acquisition of 250 acres to be used in Valhalla for a new cemetery. The next year the association built a railroad station, office, and reception room. Families could ride a direct train from Grand Central Terminal right to the cemetery, aboard special funeral cars on the New York Central (today the Metro North’s Harlem Line) Railroad.

During the 1890s the cemetery expanded and developed the first fifty acres. Notable New Yorkers began to build mausoleums, buy family plots, and erect beautiful memorials. Horse-drawn carriages brought visitors for day trips to the park-like cemetery. Even today, it looks like Central Park with gravestones. Native American names are given to plots and lakes, such as Montauk, Tecumseh, Iroquois, and Katonah. When the parkway system was laid out at the beginning of the automobile age, the new roadways led, literally, to the cemetery entranceways.

Kensico attracted notable names almost from the time it opened: clothier Paul J. Bonwit, opera star Geraldine Farrar, jazz great Tommy Dorsey, baseball icon Lou Gehrig, conductor Sergei Rachmanoff, author Ayn Rand, beer baron (and Yankees owner) Jacob Ruppert, radio pioneer David Sarnoff, and hundreds of other notables. Today there are more than 150,000 burials and the cemetery grounds have expanded to 460 acres, among the largest in New York State. The mausoleums adopt styles of Roman, Greek, Art Deco, and Gothic architecture.

How did so many entertainers end up in Kensico? Two words: Burial Grounds. The Salvation Army was the first big organization to purchase significant acreage in Kensico for deceased soldiers (Evangeline Booth, daughter of the organization’s founders and its first female leader, is interred here). In 1886, The Actors Fund purchased its first plot at the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn. In 1904, a second plot was purchased at Kensico. The Fund pays for the interment of actors and actresses. This plot contains Vivian Blaine, Ann Pennington, Blanche Yurka, and hundreds more, and still accepts burials.

But the vaudevillians, not part of “legit” theater, had other plans, and are interred separately. Where did the N.V.A. organization come from?

The National Vaudeville Association was the last stop on the train for the organized business of professional vaudevillians. Legitimate theater had “the Syndicate” which monopolized most U.S. theaters at the turn of the century, and vaudeville was no different. Edward F. Albee, the partner with theater magnate B.F. Keith, co-founded the Vaudeville Managers Association in 1900 to centralized bookings and control performers. It was a cartel from coast to coast. In 1901 it faced a collective bargaining challenge from vaudeville actors, the White Rats, and beat them. After more machinations and deals with others, Keith-Albee engineered in 1906 the United Booking Office (U.B.O.), which consolidated a stranglehold on practically all of vaudeville.

It required performers, from clowns to dancers, to belong to a new entity, National Vaudeville Artists. Failure to join, or to perform with a rival independent producer or tour, could lead to being blacklisted. The Vaudeville Artists folded around the time the U.B.O. lost power, and saw increased competition from new forms of entertainment.

The National Vaudeville Association began about 1916. At the time, thousands of performers crisscrossed the country to appear in towns big and small. Everyone knows of The Palace in Times Square, but the circuit also extended to Walla Walla, Washington, Montreal, and Palm Beach. By 1918 the N.V.A. had 12,000 members and was doing so well that it opened its own clubhouse, similar to The Lambs or The Players, at 229 West 46th Street, with 108 rooms for members. (The 1902 building still stands; today it’s a budget hotel).

The N.V.A. joined the 1919 Actors Strike that closed Broadway for a month, and led to collective bargaining with Actors Equity and producers. In 1920 an expansion program was launched that saw the association book acts in more than 200 U.S. cities and towns. The following year in Springfield, Ohio, it organized a department just to book musical comedy shows, and 40 theater owners signed on. At its peak it had 15,000 members.

Eddie Cantor was president of the N.V.A. in 1929, the most pivotal year in the organization’s short life. In 1929 the N.V.A. began burials in Kensico, as well as opening its most ambitious project: the National Vaudeville Association Sanatorium at Saranac Lake, New York (more about this hospital will be written in an upcoming post about the legacy of the N.V.A.).

The Greek-style mausoleum of Edward F. Albee is within sight of the National Vaudeville Association plot. Albee, who loathed the acting profession, is on a hilltop overlooking them.

Among the N.V.A. officers of the era was William Morris, the “dean of vaudeville” and booking agent extraordinaire. In the 1890s he founded the eponymous agency that bears his name, today called William Morris Endeavor. At the turn of the century Morris fought vaudeville monopolies and battled the “vaudeville trust” agencies headed by Albee. He handled Cantor, the Dolly Sisters, Anna Held, Harry Lauder, Eva Tanguay, Sophie Tucker, and Weber and Fields. Morris was instrumental in launching the N.V.A. and funding the hospital. Morris, who died in 1932 of a heart attack while playing pinochle with three vaudevillians at the Friars Club, is interred in the Jewish section of Kensico, Mount Hope. (Albee, who died in Florida in 1930, is also interred in Kensico).

The association had a nominal dues system in place. When performers needed it, in the era before health insurance, they could rely on the N.V.A. to help with doctor bills. Members also qualified for internment in the N.V.A. burial grounds in Kensico, beginning in 1929. The N.V.A. held fundraisers at theaters, turning over the box office to the association, which in turn supported needy members.

The N.V.A. had modest resources, which is evident in the simple burial ground. While the cemetery has provided modern signage to mark the N.V.A section, the members never erected a stone monument such as the Actors Fund undertook. In addition, the N.V.A. chose the most economical grave markers available. These bronze markers lie flush to the ground, making maintenance easier (it appears from the dinged-up markers, lawn-mowing machines roll straight across them). However, there are a number of traditional gravestones and memorials in the N.V.A. section, put up by the families of the deceased performers. Some have both an N.V.A. bronze marker and a stone gravestone.

Who is buried in the National Vaudeville Association burial ground? I estimate 150-200 graves are here, and I have photographed and documented most of them. Such as:

These are five names. I’ve researched about 75 so far. The most recent burial I saw was for Frances Cunningham Moyer (1901-1996).

In the coming months I’m going to be writing brief biographies and adding photos of nearly 100 of the N.V.A. graves. If you are interested in updates, keep checking back on this site, and follow me on Twitter and Instagram. They will be published weekly, with photos of the graves and any other ancillary material I dig up.

If the Kensico Vaudeville Project takes off, I’d like to take a group to visit the cemetery and clean up some of the grave markers. As you’ll see in the coming weeks and months, not only are the performers forgotten, so are their graves. I welcome any feedback and you can contact me.

Project Updates and Biographies are posted here.

Sources: