Kensico Vaudeville Project #11

Name: Richy W. Craig, Jr.

Act: Comedian, Dancer, Singer

Born: November 17, 1902, Manhattan

Died: November 28, 1933, Manhattan

What could be worse for a performer: suffering through tuberculosis for seven years, or watching Milton Berle steal your act? To Richy W. Craig, Jr., both happened. When he was buried in the NVA burial ground he was only thirty-one years old.

Richy Craig, Jr. gravestone in the N.V.A. plot.

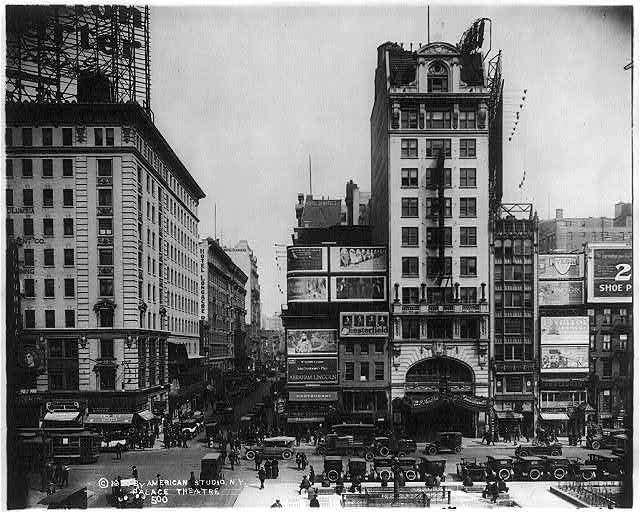

The New York Post called Craig “a vaudevillian of dry humor, sharp wit, and easy delivery.” Craig was one of the early vaudeville stars to transition to talking pictures. He rubbed shoulders with the Marx Brothers, George and Ira Gershwin, Texas Guinan. He wrote for Bob Hope and was a popular emcee at The Palace. But with only brief film spots, he’s virtually forgotten today.

Billy Reed, a burlesque and vaudeville dancer who appeared on the same bill during Prohibition, said Craig invented stand-up comedy as we know it today. In 1953 he wrote,

A young fellow by the name of Richy Craig, Jr., was soon to introduce a new type of wit and humor to the theatrical world. Richy was probably the first young comedian to walk out on a stage with no make-up, in an ordinary street suit, and get laughs from an audience. This he did in burlesque while comedians in those days had red noses and baggy pants. Richy Craig’s credo was, “If you’re funny you don’t need any help—and if you’re not you need plenty of help.”

Craig was born into a vaudeville family on November 17, 1902, as Richard Reichman. His father, Richard Craig (a.k.a. William Reichman), was a burlesque dialect comedian, his mother Dorothy Blodgett, an actress in musical comedies. Father and son adopted Craig as their stage name.

Showbiz lore claims young Craig was put in boarding schools while his parents traveled on vaudeville circuits. The tale is a teenage Craig quit high school, visited his mother in her dressing room in Buffalo, and begged to be allowed to join the family business. She relented and two years later he played The Palace.

Richy Craig, Jr. Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

Craig was paired with a young Joe Besser, many years later a fill-in member of the Three Stooges. Besser and Craig met in 1920 when Craig was the emcee at Loew’s Brooklyn. Besser was on the bill and Craig fed him lines. Producers were so impressed by the chemistry they packaged them as a team and sent them on the road for a year.

Around 1924 Craig married Edith “Edie” Marie Halls, a seventeen year-old rising star. The couple had no children. The couple lived out of a suitcase their entire marriage.

Craig spent the Roaring Twenties performing and writing. He also contracted tuberculosis, a common disease in the theater business of the era. Saranac Lake in upstate New York was the location for tuberculosis hospitals, and the National Vaudeville Association opened a home there for sick performers. As the Twenties drew to a close, Craig checked in for eight months to recover. He spent the time writing gags and bits that he sold off to other comedians. When his health improved he returned to monologues and stand-up comedy.

When the 1931 professional baseball season began in April, Richy was on the radio with future Hall of Famer Hack Wilson, at the time a centerfielder with the Chicago Cubs. Appearing nationally on the ABC network, sponsored by Blue Ribbon Malt (this was during the waning years of Prohibition), the slugger was a studio guest with Richy, called “the Blue Ribbon Malt Jester” on coast-to-coast radio.

In November 1931 it was announced Craig and Jack McGowan were writing the book for a new musical comedy. George Gershwin was writing the music and Ira Gershwin the lyrics. Craig had been in Lake Placid for five months trying to cure his tuberculosis. However, Craig was too sick to participate and Pardon My English did almost no business when it opened in 1933.

The final full year of his life, 1932, was one of the most important of Craig’s life, even if it did not cement his name in the history books as a New York performer. In January, Vitaphone signed him to a one-picture contract for a comedy short for him to write and star in. This may have been You Call it Madness.

In April 1932 Craig was touring on the R.K.O. Vaudeville circuit, as the top-billed stage comedian. R.K.O. screened Prestige starring Ann Harding and Adolph Menjou, backed up by vaudeville comedy, musicians, and dancers. Craig was billed as “the world’s unknown humorist” offering a comedy monologue.

In June 1932 Craig opened at the Shubert Theatre in his last show on a legit stage, in a splashy musical comedy review called Hey, Nonny Nonny. Craig performed the title song, written by Ogden Nash, one of many wordsmiths in the credits. One of the contributors was E.B. White, at the time on The New Yorker. Ruth Gordon, Frank Morgan, and Ralph Sanford filled out the cast. It lasted a month in the hot summer in the days before air conditioning.

From the Shubert, Craig went back to his roots. The week of July 9 was the last full week of straight vaudeville at The Palace. Craig was on the bill with all-star performers. Afterwards movies and acts were shown together. Craig had started selling material to other comedians when he was too sick to perform. Among those he wrote jokes for was Bob Hope.

At the same time his act was being stolen. Milton Berle, as a rising young star, had developed a notorious reputation for stealing material. Walter Winchell reported on the backstage feuds, led by Craig, who had his act plundered. In August 1932, Winchell wrote, “To settle the feud between Berle and Craig, suggests Al Schwartz, let’s remain neutral, and call Berle ‘The Thief of Bad Gag.’ ”

But Craig was furious. Winchell reported that an old friend approached Craig in front of the Palace and asked the comedian why he was angry with him. “Well, I’ve reason to be,” replied Craig. “When Milton Berle played the Capitol, you didn’t even send me a wire of congratulations.”

Craig listened to Berle’s act and was shocked by how much material the younger man swiped from him. Winchell reported Craig wrapped up a bundle of his own publicity photos and sent them to Berle with a note, “Put these in the lobby and go the limit.” Berle got the photos and wired back, “The photos you sent me were so unsoiled that I am sure they have never been used. It should be a novelty to you to see them in a lobby.”

Winchell stoked the feud in his column, which was read by everyone in the entertainment business at the time. Winchell wrote, “Berle visited Richy backstage the other afternoon and laughingly replied to the latter’s reproach, ‘Well, I think I’ll steal your wife, too.’ At which the lovely Mrs. Craig chirped, ‘What would you have to offer me for amusement, Richy’s old jokes?’ ”

While the success was piling up, Craig’s health was sliding and couldn’t be hidden from the public. Syndicated columnist O. O. McIntyre wrote in December 1932, “Richy Craig, Jr. looks so fragile in a close-up.” In June 1933, Winchell wrote of Craig’s illness, “In California for his failing lungs, isn’t trying too hard to live. Too much ‘jolly times.’ “

Meantime, Craig and Edie split up. On Oct. 10, 1933, Winchell reported, “The Richy Craig Jrs. have finally put themselves asunder.” Gossip columns said Craig had fallen under the spell of a beautiful “metaphysician” who convinced him to stop treatment. Craig left his wife in Hollywood and went to New York to appear on the radio. He was on Fleischmann’s Yeast Hour (also known as The Rudy Vallée Show) on November 9. Craig and Mildred Tully performed a scene from Say It Isn’t So. It was his last radio show. Sadly, you can hear Craig coughing in a rare clip.

[4:50 mark of this extremely rare vintage recording to hear Craig perform solo. 25:00 mark for Craig and Tully]

Craig checked into a hotel in Manhattan. His metaphysician called a doctor and abandoned him. Craig was taken to New York Hospital but it was too late. He died on November 28, 1933, ten days after turning thirty-one. His remains were brought to Kensico and interred in the N.V.A. burial ground with a stone marker.

On December 17, 1933, Bob Hope headlined a benefit show for Craig’s widow at the New Amsterdam Theater. It was a testament to how beloved Richy Craig, Jr. was by his peers. The all-star list of performers that night: Fred Allen, George Beatty, Jack Benny, Eddie Cantor, Leo Carrillo, Bob Hope, Bert Lahr, Abe Lyman and his band, Walter O’Keefe, Jack Pearl, and Walter Winchell.

Kensico Vaudeville Project

Project Updates and Roster of Names

If you are interested in updates, keep checking back on this site, and follow me on Twitter and Instagram. New material is published frequently, with photos of the graves and any other ancillary material I dig up. I welcome any feedback and you can contact me.

Photo: Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Richy W. Craig, Jr.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 6, 2017.