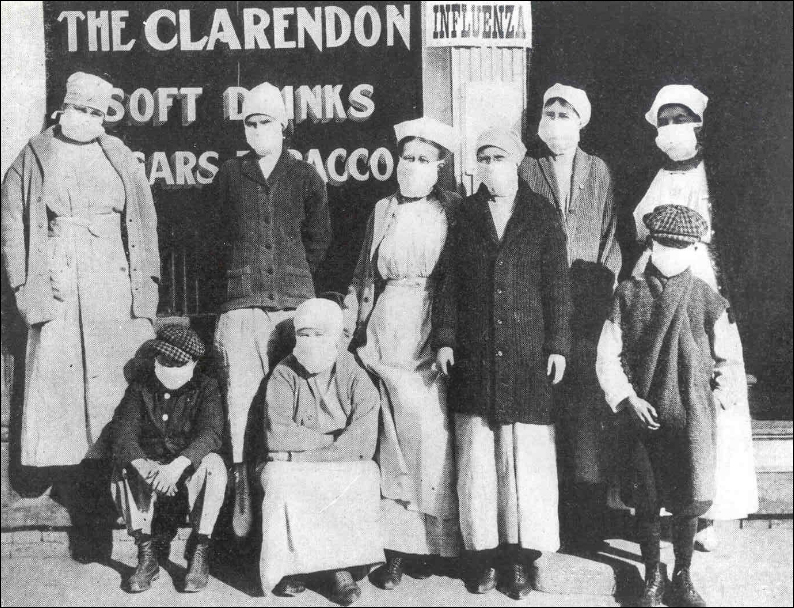

My research on Starrett concluded, and then I realized that he died during the beginning of the pandemic, was the in the median age of victims, and his death attributed to pneumonia. He died during the pandemic and I didn’t realize it until now.

I actually first got a glimpse of the pandemic while researching the 2014 book I edited, Dorothy Parker Complete Broadway, 1918-1923. She was a drama critic at the time when theaters were shuttered due to the spread of the disease. She wrote in Vanity Fair for the December 1918 issue:

There is always this to be said for the epidemic of Spanish influenza—it gave the managers something to blame things on. Whenever a manager saw that all was practically over with a play, he hid his aching heart under the guise of noble solicitude for the public welfare, and, with an air of, “It is a far, far better thing that I do than I have ever done,” announced that the play would be removed, owing to the epidemic. If you are one of those who must ever go about the world finding good in everything, hold the thought that the Spanish influenza has helped many a play to make a graceful get-away.

That is classic Parker, using humor to diffuse a grim situation. At the time, Parker’s husband, Edwin Pond Parker II, was a private in the United States Army, driving an ambulance in France. He returned unharmed.

Starrett is an interesting fellow, and I enjoyed researching about his life cut short. He certainly was on the rise for creating new and exciting architecture with his brothers, who all went on to great achievements. I included a section on him in my 2015 book, The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide.

When the first guest checked into the Algonquin Hotel in November 1902, nobody could be prouder than the young architect who designed it, Goldwin Starrett. Just twenty-eight, it was his first major project in Manhattan. Starrett was born September 29, 1874, in Lawrence, Kansas. He grew up in Chicago and was one of five brothers to go into architecture, construction, and engineering. Starrett studied engineering at the University of Michigan, where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in 1894. Upon graduation, he followed the path of his two older brothers to a position in Chicago with Daniel H. Burnham & Co. Starrett went on to become one of Burnham’s principal assistants. Burnham was behind the Chicago World’s Fair and the White City, and figures into Erik Larsen’s great book, The Devil in the White City.

Four years later Goldwin moved to New York and joined his brother, Theodore, at the George A. Fuller Construction Co. as superintendent and assistant manager. In 1901 the Starretts and their brothers, Ralph and William, formed their own company, the Thompson-Starrett Co. The brothers built the Algonquin between April and November 1902. Incredible as that may seem, from the time the foundation was dug until the first guest checked in was only nine months.

Goldwin Starrett next took an engineering position with the E. B. Ellis Granite Co. in Vermont, which supplied the stone for many important New York structures, including the Woolworth Building. A few years later he returned to New York and formed an architectural firm with Ernest Alan Van Vleck. Their office was located on the 21st Floor of 8 West 40th Street. Among the landmark buildings designed by Goldwin Starrett that are still standing today:

1908: High-rise Everett Building, 200 Park Avenue South;

1911: Hahne & Co. department store, 609 Broad Street, Newark;

1914: Flagship Lord & Taylor store, 424 Fifth Avenue;

1916: Fourteen-story, white terra-cotta, Hill Publishing Building, 475 Tenth Avenue;

1916: 820 Fifth Avenue, a thirteen-story luxury apartment house. In 2009 one apartment there sold for $40 million.

On May 9, 1918, Starrett died of pneumonia at his home in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. He was forty-three years old. Two of his brothers went on to build the Empire State Building.

Today, Suite 1215 of the Algonquin Hotel, one of the nicest rooms in the hotel, is named the Goldwin Starrett Suite.